On Friday, Columbia College faced off against Stephens College in a doubleheader. After a...

Lori Nair, a female business owner in Tulsa, started her shop by chance 22...

The Greek economy is facing several domestic challenges that continue to overshadow its prospects....

A recent report has brought to light the violent eviction of Indigenous people from...

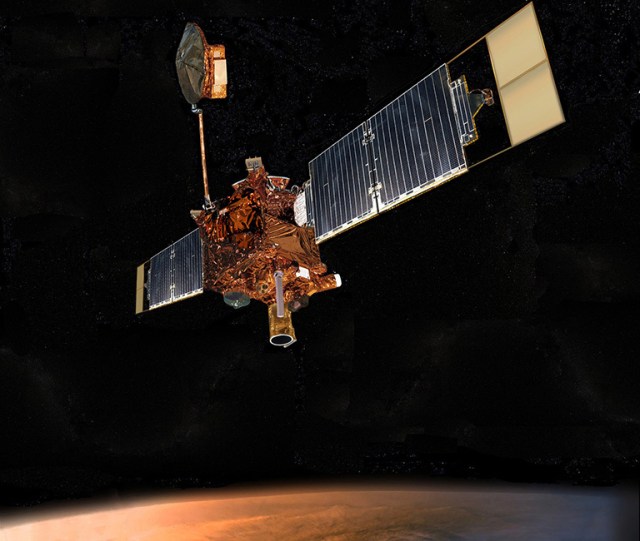

Mars Global Surveyor was a revolutionary spacecraft that transformed scientists’ knowledge of Mars. For...

Poland has secured a 250-million-euro agreement with the World Bank to fund its Clean...

Congressman Steve Cohen (TN-9) announced that Memphis Health Center Inc., Porter-Leath, and the Shelby...

On Friday (19), Brannon Kidder, Brandon Miller, Isaiah Harris, and Henry Wynne achieved a...

Drake’s “Push Ups” sparked a rap beef between him and Rick Ross, who responded...

A new tool developed by Japanese researchers promises to help bosses predict which employees...

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/YZC6NU4NF5EFZN43FN7FWZ2GN4.jpg)